When it comes to wildlife conservation in Australia, most traditional approaches are initiated and managed by government departments. Needless to say, they are supported by allocated public funding, determined by national budgeting plans. Such projects are and have continually proven to be subjected to funding constraints, political restrictions and fixed responses across spatial scales, i.e state borders. Not to mention, the proportion of public land allocated as protected areas or reserves are very small, thereby limiting the extent of any positive wildlife conservation impacts.

Meanwhile, most of Australia’s land is privately owned but landholders have not been included as partners for wildlife management. Hence, George Wilson, principal of Australian Wildlife Services and adjunct professor at Fenner School of Australia National University, is advocating for trials to manage wildlife on private lands and promote biodiversity as potential assets rather than a liability to private landowners. Drawn by the novelty and potential benefits of this proposal, I asked to be a part of the team to help research and further develop its potential.

Specifically, I was researching on several threatened species in New South Wales (NSW) and looking for possible translocation from overabundant populations or breeding programs elsewhere in Australia into NSW. The rationale is that such translocations and reintroductions have been successful in predator free facilities such as Mulligans Flat, so it is possible for private landowners to undertake similar projects as well. If successful, private landowners can be a supplement or even significant contributor to wildlife management traditionally ventured only by government.

Figure 1. An Eastern Bettong in Mulligans Flat. (Source: Dr Adrian Manning in an ABC article)

Examples of threatened species that I researched on included Phascolarctos cinereus (Koala Bear), Bettongia gaimardi (Eastern Bettong), Dasyurus viverrinus (Eastern Quoll), Myrmecobius fasciatus (Numbat), Sarcophilus harrisii (Tasmanian Devil) and Bettongia penicillata (Brush-tailed Bettong/Woylie). The information was then placed into mind maps.

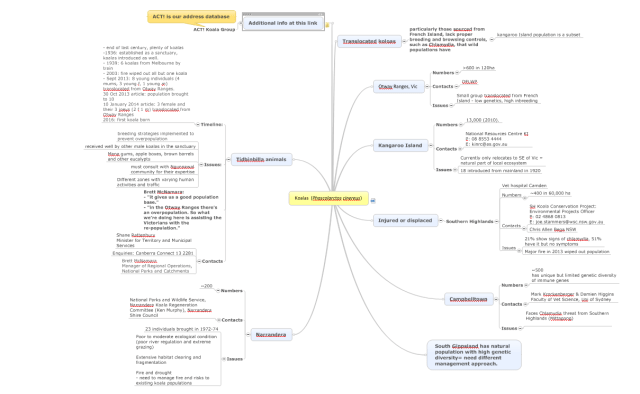

Figure 2. I entered relevant research into mind maps to create a log of all the species. This image shows a mind map I created for koala bears.

What became most evident to me was that every species had its own specific requirements and issues, hence any solution could not be applied uniformly across. For example, the koala bear is overly abundant in Victoria, resulting in extensive damage on foliage cover, and ultimately, tree death. Logically, we could translocate them into NSW, where koala bears are endangered. However, prior to the translocation process, we must address the loss of genetic diversity in these Victorian populations due to the founder effect, as well as the spreading Chlamydia outbreaks. The Tasmanian devil also suffers from a facial tumour disease, which scientists are actively trying to remove. However, on top of that, the Tasmanian government disapproves of programmes that aim to translocate healthy devils to anywhere but Tasmania. At the moment, regulation stipulates that Tasmanian devil translocation programmes require the approval of the Tasmanian government first. Lastly, how will the devils interact with feral foxes, and how will Australia’s other native herbivores fare? These questions must be addressed before wide-scale interventions are implemented.

This is where the advantages of private wildlife management come in. Borrowing from Dr Stuart Whitten’s talk on off-reserve conservation, an environmental economist at CSIRO Ecosystem Services, managing smaller numbers on smaller land areas allow for considerable flexibility in processes, responses and outcomes. Thus, conservation strategies can differ according to the individual goals, location, capacities and constraints. When customised and precise to the circumstances of these land owners, as opposed to stringent state-prescribed policies, conservations objectives are perhaps more likely achieved. Indeed, private investors are motivated in ensuring benefits/profits, which can form a strong sense of ownership for the ventures they decide to embark on.

Having said that, there are risks associated with the private sector’s profit-driven mentalities. What happens when private owners prioritise profits over wildlife conservation or welfare? Can the public or government authorities intervene? Should the public pay to support continued maintenance on wildlife on private lands, or abandoned wildlife?

Currently, there are government-regulated programmes such as Australia’s agriculture environmental schemes, which pay private owners to adopt environmentally-sound land management. Pannell’s public private benefits framework suggests that ideally, there should be maximum public benefit with very slightly negative net private benefits. The argument is that society should be paying for interventions that benefit the public, without paying extra for private incentives. The difference here between programmes such as AES and private-initiated projects, is that private owners are forking out the costs and absorbing risks. Hence, it is justifiable for them to work towards personal benefits. How then should Pannell’s graph differ? Or perhaps, a new model needs to be developed in order to figure out when, where and how interventions are needed to produce the most justifiable and effective outcome.

Indeed, more research and preliminary preparation must be achieved before any real action to take place.

Nevertheless, I am inspired by the idea that the private sector can be more involved in wildlife management, not only because it can address the shortfalls in public expenditure, or because it can contribute to the conservation of threatened species. I am most motivated by the vision of a culture of ground-up initiatives, whereby people take the ownership of biodiversity conservation, and the responsibility of looking after our planet Earth.

George has done such a magnificent job developing and researching on opportunities for the public sector to be involved in wildlife conservation, especially in the face of increasing biodiversity loss and extinction. Advocating landholders to breed their own populations of threatened species is only one approach, and there are potentially numerous more that we just have not thought of because we did not think it possible. But when government-led initiatives have proven time and time again to be less effective than desired, why not give the private sector a shot? It may not be the answer to all biodiversity loss problems, but it certainly has the potential to contribute significantly, especially for iconic, threatened species. Hence, I would like to take this opportunity to thank George for giving me this opportunity and introducing me to this existing new venture. I am excited for what is yet to come.

*My volunteering experience occurred from 21 September to 12 October.

Author: Judith Soh, u5498035 (2016)

Author: Judith Soh, u5498035 (2016)

It’s an interesting, and sometimes contentious, issue. Thanks for sharing Judith. Phil